Saturday, June 7, 2014

A Brief Look at the Werewolf Through History

Do you like this story?

Since ancient times, the fusion of man and wolf has been the stuff of legend and folklore (“wer” was the word for “man” in old English, with “man” being completely gender neutral). Virtually every culture across the globe has its own werewolf mythology, with this beastly shape-shifter being one of the oldest monsters to terrorize humans. Werewolf legends span so far back that their existence almost certainly predates recorded history. It’s a safe bet that werewolves have been freaking people out since our ancestors were huddled around puny campfires, in hopes of staving off the evil creatures that went bump in the night.

In reality, wolves rarely attack humans, though this is partially a function of their greatly diminished population, and also that they aren’t stupid, and quickly learn not to mess with humans. The only time that wolves typically pose a real threat to humans these days is during especially brutal winters when food is scarce, if one is wondering alone in the woods in the evening or the like. (Such as recently: A Blogger’s Tale: In Which the Protagonist Decides to Step Away from His Computer for a Day and Comes Seconds Away from Being Consumed by Wolves)

Despite this, wolves have been cast as the blood-lusting bad guy whether they earned that reputation or not.

In

any event, one of the earliest written accounts of a werewolf comes to

us courtesy of Herodotus in 440 BC where he describes a tribe of people

in Scythia who annually transformed into wolves.

In

any event, one of the earliest written accounts of a werewolf comes to

us courtesy of Herodotus in 440 BC where he describes a tribe of people

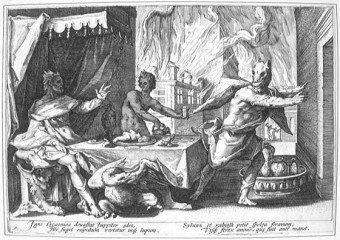

in Scythia who annually transformed into wolves.About 500 years later, Ovid shares the tale of King Lycaeon. Zeus decided to pay the king a visit, but His Majesty didn’t believe for a second his supposedly divine guest was the real McCoy. King Lycaeon decided that feeding his visitor human flesh during a banquet held in his honor would be the best way to prove his theory. If Zeus was really a god, he’d presumably see through the ruse.

Cannibalism inspired the same reaction back in the day that it would in modern times. It also didn’t help that Lycaeon attempted to kill Zeus in his sleep. Needless to say, Zeus did not take kindly to Lycaeon’s behavior. He turned the unfortunate king into a werewolf, figuring if Lycaeon enjoyed serving and eating human meat so much, he would be better off inhabiting the body of a wolf, since they already shared the same dietary preferences. Tough luck, Ly.

Werewolf legends spread all over Europe and Asia with all the various myths sharing two common threads: werewolves were inherently evil and they had a predilection for human flesh. Beyond this, it seems anything goes – a werewolf could be of either sex and shape-shift permanently or intermittently. Some legends assert that a werewolf would need the actual skin of a wolf to make the change-over, while others assure us that the skin of a hanged man would do the trick. The association between a full moon and shape-shifting into a werewolf was not part of the original folklore -it came much later.

There were several supposed “cures” that made the rounds, many that involved complicated recipes and verses that one should recite to said werewolf. Feel free to ponder if one is a fool or a saint for attempting to perform a half-baked exorcism on a hairy, feral monster that is intent on wearing your intestines as a necklace.

Once Christianity displaced Paganism as the popular religious affiliation of most Europeans, werewolves were lumped in with – you guessed it – Satan. The head honchos of the Church, who clearly were in dire need of hobbies, spent untold man-hours debating whether werewolves literally took on the form of a wolf, or whether Satan just tricked us into thinking they did. They finally came to the conclusion that Satan was just messing with our minds.

So, did this pronouncement from the Church end the spread of folklore starring the werewolf? Hardly. Our medieval ancestors didn’t have terrorists, the Westboro Baptist Church or the Kardashians to hang all their fears on, so they had to make due with archetypes such as witches, goblins and werewolves. Reports of werewolf attacks skyrocketed in Europe, and remained constant right through the Renaissance, when we encounter the tale of one of the most notorious wolf-men of them all.

A man named Peter Stubbe, who resided in Northwest Germany, held the dubious distinction of being the Ted Bundy of his time, or at least he confessed to such (there is some debate whether it was actually a political execution). Whatever the case, a spate of wolf attacks led villagers who were hunting the pack straight to Peter Stubbe, who supposedly didn’t resist as he was captured.

After a date with the torture wheel, Stubbe admitted to making a pact with the devil, and committing the crimes of murder, cannibalism and rape. He claimed he’d spent the better part of the preceding two decades killing kids (including his son) and livestock, then eating the remains, while repeatedly raping his own sister and daughter as a sideline. Beyond that, he claimed he’d murdered pregnant women and eaten their fetuses, which were “dainty morsels.”

He claimed thanks to powers given to him by the Devil, he could transform into “the likeness of a greedy, devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body, and mighty paws.” One wonders why he didn’t transform into such a mighty creature and eat his torturers.

Whether any of his crimes happened or were simply a product of confessions given while being tortured, the aghast community responded by pulling off Pete’s skin in various places on his body with red-hot pincers. They then ripped off his arms and legs (smashing them after so he couldn’t regain their use if he came back from the dead) and then decapitated him.

For good measure, his daughter and mistress were also brutally executed via flaying and strangling. The bodies were all then thrown into a fire.

Even though Stubbe was dead and gone, his high-profile gruesome story and execution ensured that werewolf legends would remain a part of the collective conscious for some time to come. Because of this and other such stories, there are those that believe werewolves are actually an attempt to explain the phenomenon of the serial killer, as people found it easier to believe that an animal – or monster – was responsible for crimes considered too heinous and unspeakable for any human being to commit.

For instance, in 1521, two men named Pierre Burgot and Michel Verdun were executed as werewolves, when in actuality they were a couple of serial killers who’d joined forces. In France, another self-confessed serial killer, Gilles Garnier, or the “Werewolf of Dole,” was put to death in 1573. There are many other cases such as these that took place all over Europe during that period. Is it a coincidence that the wolf population was also at its zenith at the same time? Were people confusing the behavior of animals with animalistic behavior?

The legend of the werewolf lives on to this day, albeit in more cartoon-ish, less intimidating forms. Werewolves in modern mythology tend more towards the introspective anti-hero, constantly battling with their dark, untamed side; or smooth-chested hunks of young beefcake that compete with emo, sparkly, ephebophile vampires for the affection of an expressionless, underage, human female devoid of anything resembling acting skills… The only scary thing about any of this is the prospect of losing the ability to change the channel.

Still, on dark nights when wispy clouds race over the face of the moon, it’s not hard to imagine the primal fear our ancestors felt when they heard the wild howl of the wolf. After all, even in our enlightened age, we all still run like mad up the stairs after shutting off the lights in the basement. Not this time basement monsters. Not this time.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Responses to “A Brief Look at the Werewolf Through History”

Post a Comment